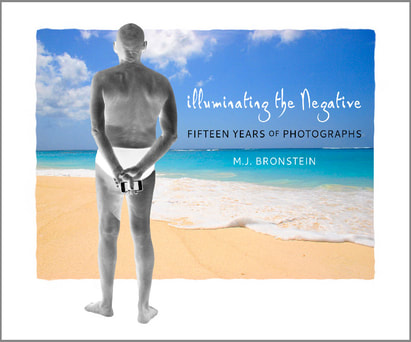

ILLUMINATING THE NEGATIVE : IN THE STUDIO

An Interview with Director/Curator Suzette Lane McAvoy

An Interview with Director/Curator Suzette Lane McAvoy

SLM: What first inspired the Negative Series?

MJB: The seeds for the series were planted at least 25 years ago, when I was fourteen or fifteen years old, in high school, and working in a darkroom. The darkroom was my refuge. I loved being there, I loved working with negatives. I have strong memories from that time of looking at negatives on a light table. I was never really as interested in looking at contact sheets as I was in looking at negatives through light. So that was probably the beginning...then the fascination with negatives just kind of lingered in my mind for a while, until years later when I tried to make negative photographs in the darkroom.

SLM: You tried to make your own negatives and print them?

MJB: Yes, I would make a print of an image and sandwich that print on top of a piece of photo paper, so essentially you’re making a contact print, similar to the early practice of using paper negatives. That’s really what I was doing…you take your positive and then you sandwich it onto a piece of fresh paper and then you shine the light through it and you expose it to create a negative print.

SLM: So when was this, that you first began making negative prints in the darkroom, what year was this?

MJB: That would be maybe fifteen years ago, but it was something I kept coming back to. I remember playing with the idea of making negative images when I was living in Italy during the early 1990s. I was using slides, which are positives, and putting the slides in the negative carrier of my enlarger so that I could print the positive slide as a negative image.

SLM: Is part of the challenge then how to display the negative image in a way that the viewer can experience something of that same moment in the darkroom?

MJB: I think that’s a great way to put it... For me, the look of the negative is entrancing. It seems to glow, and it has a different palette, especially in the mid-tones. It has a hard, crisp line on the highlights and then where the mid-tones and highlights meet you have a softness.

SLM: In A.D. Coleman’s essay, Negative Capabilities, which he wrote in 1999, he describes photographers as often working “in another perceptual dimension” because they spend so much time looking at their own negatives. Do you identify with that?

MJB: Yes. You are in another perceptual dimension when you are looking through a camera, framing the world, creating images, and then viewing your negatives...you're looking at a special kind of record, an imprint of light.

SLM: He also writes that “one could argue that there’s nothing more purely photographic than the negative image.” Do you agree?

MJB: Yes, that's perfect. Because the negative holds all of the details that produce the eventual positive, yet oftentimes, information is lost in the journey from negative film to positive print. For me, working in the negative reveals qualities and details that are often unseen in the positive. And it takes me back to the source, which is light.

SLM: So working with light is what inspires you?

MJB: Absolutely. I'm working with light, directly and palpably. After all, the word “photography” means "drawing with light." Photographers are attracted to the world of the camera for all sorts of reasons. Some really love the technical side, the equipment, but I’ve never really been a camera lover... for me it’s more elemental or primal—it’s about light and time and images. Early on I worked as a newspaper photographer, printing my own work and the work of others—I spent nearly fifteen years in the darkroom. Anyone who has seen an image rise up out of a bath of chemicals knows that the darkroom is another world—it’s a magical place to be.

SLM: And hand-coloring your prints has been an ongoing practice in your work, hasn’t it?

MJB: Yes, it has. Even in art school, I was often trying to interact with the photographic print somehow; I rarely took straight photographs. I was always trying to do something else with the print afterwards. In the early years, I played with chemical toners, and then, soon after, I started using liquid watercolors to selectively colorize an image. I started out studying painting and sculpture—the focus on photography came along later—so painting and bringing color into the print by hand is something that goes back to my earliest work.

SLM: So you don’t necessarily embrace Ansel Adams’s statement, “the negative is the score; the print is the performance.”

MJB: Well, for Ansel Adams and his work that statement is perfect. For me and my work, the print is more like a painter's canvas. I admire a beautifully printed image, but for me it’s never been quite enough, it's a starting point rather than the goal. It may be because my art heroes have always been more painters than photographers—Paul Klee, Karel Appel, Matisse, Bonnard—mostly European painters. There are some photographers that have really influenced me, Roy De Carava, for one was a really important early influence, but it’s the way painters approach what they do that is closer to the way I approach what I do.

SLM: Can you describe how you use color in your work?

MJB: There’s a Miro quote that I like—“I try to apply colors like words that shape poems, like notes that shape music.” I start with my image as a base, usually black and white, and then I selectively colorize areas so that with the color, I'm pulling parts of the image forward, and sending other parts back. I'm emphasizing spaces and details, and de-emphasizing others, creating an image that directs a viewer's gaze. I never want my images to appear fantastical—I always want them to have at least one foot in “reality”—so the colors I choose, my palettes, are always grounded in some kind of physical reality.

SLM: Let's talk about First Light, you've said that of the three series within Illuminating the Negative, that this was the first to come together.

MJB: Yes, the First Light series started around the year 2000, when my son Noah was in elementary school. I photographed him and his friends constantly in those days, in the years before adolescence, when their worlds were rooted in play. It’s the transience of childhood, the ephemeral nature of it that the series is about. And really, that’s what photography is about at its core—it’s about transience, about capturing that fraction of a moment. For me, the negative image communicates this idea, very poignantly—the idea that life is here, and then it’s gone, that every single moment is here, and then it’s not.

SLM: Along these same lines, I know that your longstanding study of yoga has had an influence on your work. Can you say something about that?

MJB: The study and practice of yoga has had a big effect on my life and my art. Even the words that infuse the yoga world are the words that interest me in my art world. The idea of being filled with light and air, or moving from the inside out—these are metaphorical ideas and images that are at the heart of a yoga practice, and they are the ideas that inform my image making.

SLM: This focus on the realms of light and air seem to be especially reflected in your Infinite Horizons series.

MJB: Yes, and these images have been the easiest images for me to make. They do speak very directly to the spiritual world, the world outside of us and inside of us—which is of course the same world. The images in this series are meditative. The focus is on the sea and the sky, the wind and the light, and a number of them are titled Meditation.

SLM: So what makes a good photograph for you?

MJB: Well, the first word that comes to mind is transporting. Just as in a good novel or a beautiful piece of music, a work of art should take me someplace. When I'm looking at a powerful work of art, there is the sense that the artist was fully, utterly present in the making of it—and at the same time, sliding out of the way, so that the art can happen. So it feels like it came through the artist, there's a sense of channeling. I want to feel a sense of mystery, like "how could this have come to be?" Not in the technical sense, as in "how was this made?"—but beyond that, to a place of wonder. When I look at my own work, when I come back to it and I can't really understand how it came to be, then I know that something special happened—I know I was in the groove.

Suzette Lane McAvoy is an Art Historian and Curator who writes frequently on the art and artists of Maine; she is the former Chief Curator of the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland and the former Director of the Center for Maine Contemporary Art.

© 2011 Bronstein / McAvoy

Monograph 106 pages

five collections of photographs created between 2000 and 2015 Site Seeing • Mother and Child • Holding On Letting Go • Infinite Horizons • First Light

preview and purchase HERE

MJB: The seeds for the series were planted at least 25 years ago, when I was fourteen or fifteen years old, in high school, and working in a darkroom. The darkroom was my refuge. I loved being there, I loved working with negatives. I have strong memories from that time of looking at negatives on a light table. I was never really as interested in looking at contact sheets as I was in looking at negatives through light. So that was probably the beginning...then the fascination with negatives just kind of lingered in my mind for a while, until years later when I tried to make negative photographs in the darkroom.

SLM: You tried to make your own negatives and print them?

MJB: Yes, I would make a print of an image and sandwich that print on top of a piece of photo paper, so essentially you’re making a contact print, similar to the early practice of using paper negatives. That’s really what I was doing…you take your positive and then you sandwich it onto a piece of fresh paper and then you shine the light through it and you expose it to create a negative print.

SLM: So when was this, that you first began making negative prints in the darkroom, what year was this?

MJB: That would be maybe fifteen years ago, but it was something I kept coming back to. I remember playing with the idea of making negative images when I was living in Italy during the early 1990s. I was using slides, which are positives, and putting the slides in the negative carrier of my enlarger so that I could print the positive slide as a negative image.

SLM: Is part of the challenge then how to display the negative image in a way that the viewer can experience something of that same moment in the darkroom?

MJB: I think that’s a great way to put it... For me, the look of the negative is entrancing. It seems to glow, and it has a different palette, especially in the mid-tones. It has a hard, crisp line on the highlights and then where the mid-tones and highlights meet you have a softness.

SLM: In A.D. Coleman’s essay, Negative Capabilities, which he wrote in 1999, he describes photographers as often working “in another perceptual dimension” because they spend so much time looking at their own negatives. Do you identify with that?

MJB: Yes. You are in another perceptual dimension when you are looking through a camera, framing the world, creating images, and then viewing your negatives...you're looking at a special kind of record, an imprint of light.

SLM: He also writes that “one could argue that there’s nothing more purely photographic than the negative image.” Do you agree?

MJB: Yes, that's perfect. Because the negative holds all of the details that produce the eventual positive, yet oftentimes, information is lost in the journey from negative film to positive print. For me, working in the negative reveals qualities and details that are often unseen in the positive. And it takes me back to the source, which is light.

SLM: So working with light is what inspires you?

MJB: Absolutely. I'm working with light, directly and palpably. After all, the word “photography” means "drawing with light." Photographers are attracted to the world of the camera for all sorts of reasons. Some really love the technical side, the equipment, but I’ve never really been a camera lover... for me it’s more elemental or primal—it’s about light and time and images. Early on I worked as a newspaper photographer, printing my own work and the work of others—I spent nearly fifteen years in the darkroom. Anyone who has seen an image rise up out of a bath of chemicals knows that the darkroom is another world—it’s a magical place to be.

SLM: And hand-coloring your prints has been an ongoing practice in your work, hasn’t it?

MJB: Yes, it has. Even in art school, I was often trying to interact with the photographic print somehow; I rarely took straight photographs. I was always trying to do something else with the print afterwards. In the early years, I played with chemical toners, and then, soon after, I started using liquid watercolors to selectively colorize an image. I started out studying painting and sculpture—the focus on photography came along later—so painting and bringing color into the print by hand is something that goes back to my earliest work.

SLM: So you don’t necessarily embrace Ansel Adams’s statement, “the negative is the score; the print is the performance.”

MJB: Well, for Ansel Adams and his work that statement is perfect. For me and my work, the print is more like a painter's canvas. I admire a beautifully printed image, but for me it’s never been quite enough, it's a starting point rather than the goal. It may be because my art heroes have always been more painters than photographers—Paul Klee, Karel Appel, Matisse, Bonnard—mostly European painters. There are some photographers that have really influenced me, Roy De Carava, for one was a really important early influence, but it’s the way painters approach what they do that is closer to the way I approach what I do.

SLM: Can you describe how you use color in your work?

MJB: There’s a Miro quote that I like—“I try to apply colors like words that shape poems, like notes that shape music.” I start with my image as a base, usually black and white, and then I selectively colorize areas so that with the color, I'm pulling parts of the image forward, and sending other parts back. I'm emphasizing spaces and details, and de-emphasizing others, creating an image that directs a viewer's gaze. I never want my images to appear fantastical—I always want them to have at least one foot in “reality”—so the colors I choose, my palettes, are always grounded in some kind of physical reality.

SLM: Let's talk about First Light, you've said that of the three series within Illuminating the Negative, that this was the first to come together.

MJB: Yes, the First Light series started around the year 2000, when my son Noah was in elementary school. I photographed him and his friends constantly in those days, in the years before adolescence, when their worlds were rooted in play. It’s the transience of childhood, the ephemeral nature of it that the series is about. And really, that’s what photography is about at its core—it’s about transience, about capturing that fraction of a moment. For me, the negative image communicates this idea, very poignantly—the idea that life is here, and then it’s gone, that every single moment is here, and then it’s not.

SLM: Along these same lines, I know that your longstanding study of yoga has had an influence on your work. Can you say something about that?

MJB: The study and practice of yoga has had a big effect on my life and my art. Even the words that infuse the yoga world are the words that interest me in my art world. The idea of being filled with light and air, or moving from the inside out—these are metaphorical ideas and images that are at the heart of a yoga practice, and they are the ideas that inform my image making.

SLM: This focus on the realms of light and air seem to be especially reflected in your Infinite Horizons series.

MJB: Yes, and these images have been the easiest images for me to make. They do speak very directly to the spiritual world, the world outside of us and inside of us—which is of course the same world. The images in this series are meditative. The focus is on the sea and the sky, the wind and the light, and a number of them are titled Meditation.

SLM: So what makes a good photograph for you?

MJB: Well, the first word that comes to mind is transporting. Just as in a good novel or a beautiful piece of music, a work of art should take me someplace. When I'm looking at a powerful work of art, there is the sense that the artist was fully, utterly present in the making of it—and at the same time, sliding out of the way, so that the art can happen. So it feels like it came through the artist, there's a sense of channeling. I want to feel a sense of mystery, like "how could this have come to be?" Not in the technical sense, as in "how was this made?"—but beyond that, to a place of wonder. When I look at my own work, when I come back to it and I can't really understand how it came to be, then I know that something special happened—I know I was in the groove.

Suzette Lane McAvoy is an Art Historian and Curator who writes frequently on the art and artists of Maine; she is the former Chief Curator of the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland and the former Director of the Center for Maine Contemporary Art.

© 2011 Bronstein / McAvoy

Monograph 106 pages

five collections of photographs created between 2000 and 2015 Site Seeing • Mother and Child • Holding On Letting Go • Infinite Horizons • First Light

preview and purchase HERE